A long-term study, carried out in an up-to-date waste incinerator in the Netherlands, warns about shortcomings in measurements of gaseous emissions released from waste incinerators into the air. Two-year measurements showed that short-term and instantaneous testing, currently used in waste incinerators in the majority of European countries, including the Czech Republic, is inaccurate and underestimates the real amounts of hazardous substances released into the air considerably. Attention to this fact is drawn by the Dutch expert Abel Arkenbout from the organisation ToxicoWatch, who summed up results of measurements carried out in 2015 to 2017 in several studies, the last of them published at the scientific conference Dioxin 2019. The results show a considerable discrepancy between values measured by customary methods and the reality.

Waste gas is produced during waste incineration in incinerators, that is released into the air. It comprises a mixture of various chemical substances, depending on the composition of the incineration input material. Many of the released substances are hazardous to the health and the environment, such as dioxins, furans, and other persistent organic pollutants. Subsequently, they are inhaled by the inhabitants of the incinerator surroundings, or they get into their bodies via the food chain, for example, from eggs and milk produced in the neighbourhoods of a waste incinerator. Emissions from incinerators are monitored by regular measurements, however, the Dutch study proves that this is insufficient for recording the real emissions of the most hazardous substances.

In 2013, the organisation ToxicoWatch carried out a study, results of which showed exceeding of limits of dioxin and furan concentrations in chicken eggs originating from the surroundings of the incinerator in Harlingen, in other words from a facility for energy recovery from waste, what is a current name for waste incinerators. In response to the ToxicWatch findings, the local authorities decided to carry out long-term measurements of gaseous emissions. The youngest waste incinerator in the Netherlands, put into operation in 2011, Reststoffen Energie Centrale, is the so-called cogeneration facility in the town Harlingen in the north of the Netherlands. The facility produces electricity and heat using municipal and industrial waste, but also sewage sludge and waste materials from biogas facilities.

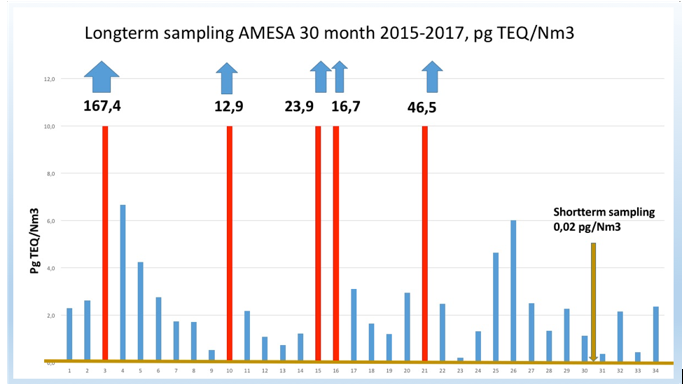

At present, dioxin and heavy metal emissions released from incinerators into the air are measured by short-term, or single, measurements. The short-term testing means emission measurement for 6 to 8 hours, at least twice a year, but with the interval of at least three months. In the case of the Dutch incinerator, short-term measurement, carried out once every half a year, was compared with long-term measurement carried out for two years. The results showed that the single measurement shows major shortcomings, and underestimates the real amounts of dioxin emissions considerably. The highest exceeding of the emission limits was found in the beginning of the incineration process starting. However, in the case of the short-term measurement testing is not carried out during this phase at all, according to Abel Arkenbout from ToxicoWatch. Also in the Czech Republic, incinerators are obliged by the law to carry out short-term testing of their emissions only. Thus, it may be assumed that long-term monitoring of dioxins would find inaccuracies and underestimations of their emissions in the case of the Czech incinerators, too.

Results of long-term dioxin measurements for 30 months. The yellow line is the emission limit for dioxins All the blue and red bars show the emission limit exceeding.

Source: Arkenbout, A., et.al. Emission regimes of POPs of a Dutch incinerator: regulated, measured and hidden issues. Organohalogen Compounds, 2018.

The study also shows the necessity to amend legal regulations laying down the method of emission measurements, in a way enabling measurements of emissions of dioxins, but also of other hazardous substances, more efficiently and with a higher accuracy. M.Sc. Markéta Kadeřávková from the Arnika Association adds: „In the ideal case, incinerator operators themselves should be interested in the as accurate and transparent measurements of their emissions as possible, thanks to which they could more easily adopt relevant measures for improvement of technologies for capturing the hazardous substances. This would better protect inhabitants and nature in the close vicinity of the incinerators, and, further, create a more open dialogue and improve the relations between the citizens and the incinerators.“ If they do this not by themselves, it will be ordered by changes of integrated permits in the foreseeable future. The fact is that the new EU regulations require introduction of long-term monitoring of dioxins in the emissions from waste incinerators.

In spite of the fact that various technologies for better capturing of toxic substances are being developed currently, waste incineration still produces other kinds of toxic waste, such as fly ash and slag, and, last but not least, carbon dioxide, contributing to the climate change very negatively. Because of that, the best waste is still the one that is not produced at all.