Oil majors and a petrochemical industry are resisting restrictions on a plastic production. They see it as yet another loss of profit after a decline of fossil fuels. They argue that recycling possibilities have improved, but according to the UN’s Environment Programme, only less than 10 per cent of the world's plastic waste is recycled, and much of the rest ends up in the oceans. An expert on toxic substances in waste and the environment, Jindřich Petrlík from Arnika, shares his views on the UN negotiation meetings in Nairobi, which took place from 13 to 19 November.

I am at the negotiation of a global convention on plastics. Plastics which have created heaps of waste in the ocean, on beaches, in rivers, and even in forests. One would think that the best way to deal with the problem would be simply to use and produce less plastic than we do now. After all, we simply don't need a lot of plastic packaging, broken PVC chairs and the like, as we can go back to good old glass, wood or metal, which last longer and are easier to reuse.

But that is not what the oil powers, from Saudi Arabia to Russia, are saying. Let us add India, Iran and China, which, although they do not extract oil, produce plastics on a large scale and flood the world with cheap trinkets. All of them do not wish to see any restrictions on the production of plastics, and therefore polymers.

I believe that many industrial managers in Europe, including officials in the Czech Ministry of Industry and Trade, agree with them. Because the vast majority of plastics are made from oil products. The largest producers of raw materials for plastics in the Czech Republic are, for example, Unipetrol Litvínov or Spolana Neratovice, which, incidentally, occupy the first places in the list of the largest polluters published annually by the Arnika association.

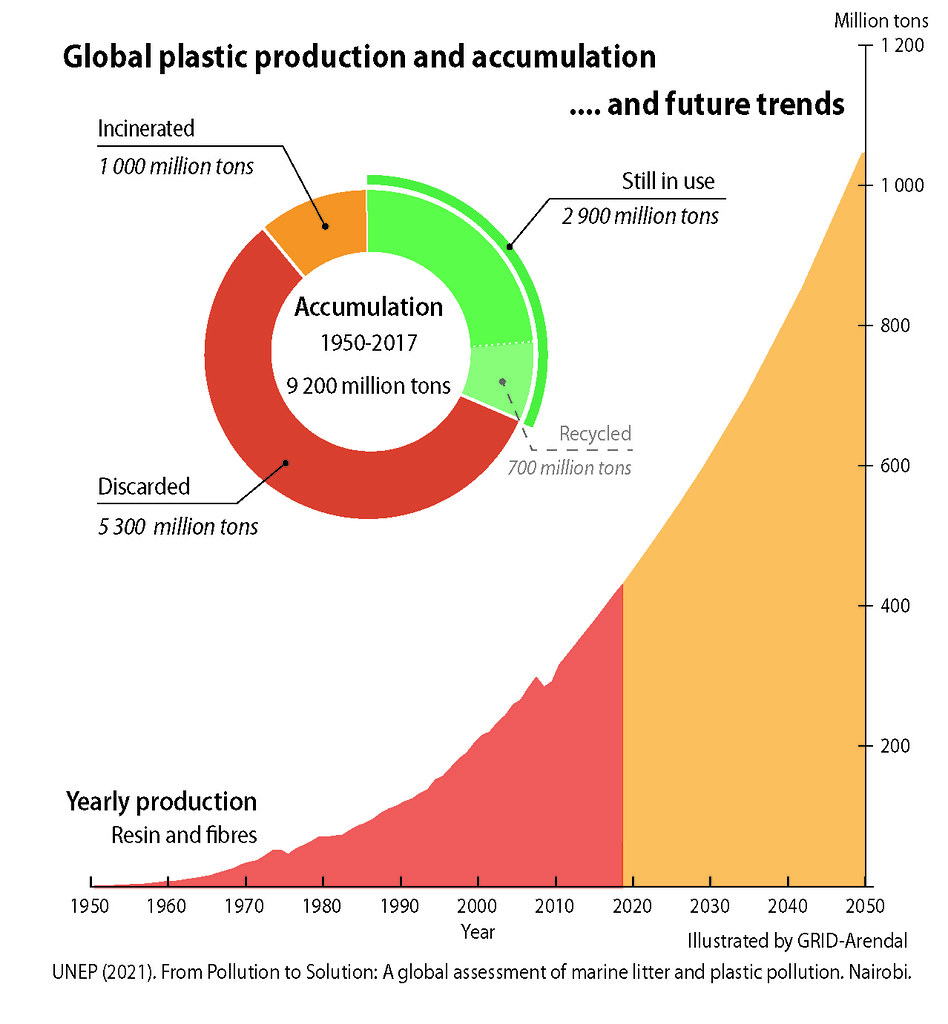

To simplify the cynicism with which the aforementioned 'oil community' thinks about the future: they either want to fry us (oil as a fuel is a source of greenhouse gases) or drown us in plastic. Global production of plastics is expected to more than double (see graph in the figure). If they drown us in plastic, they will finish us off by burning it in the form of plastic waste or fuels made from it, which is the solution proposed by the plastics and chemical industries, albeit called chemical recycling.

Although they have agreed to negotiate a global plastics convention and are recognising what is visible and undeniable, that is the world overwhelming by the plastic waste, they want no restrictions on their oil, plastic and chemical business. They claim that the problem is not the overproduction of plastics, but only the unsustainable management of waste. But would not admit that products made from “cheap” oil have simply pushed out more environmentally friendly but seemingly more expensive options – such as glass packaging, wooden toys or packaging-free sales – from the market.

The problem with plastics is all the more complicated because many of them have to include additional, often toxic, substances added to make for example PVC either soft (e.g. for flooring or inflatable toys) or hard enough (window frames, pipes, etc.). The ‘oil community’ does not want to regulate these toxic additives too globally either and generously suggests that this can be left to national legislation. The bottom line is that national legislations are often weak against the global market and if they are not weak, then not always does any given country have the resources to control toxic substances in imported products. That is what the opponents of global regulation are banking on.

An individual consumer and many poor nations have no choice but to accept this dictate of cheap plastic packaging. And, as the Fiji delegate representing a community of small island nations said, states pushing for zero restrictions on the polymer production and zero control of related toxic substances are simply leaving the burden on the weakest and most vulnerable. “This is an immoral act,” he concluded his speech at the Nairobi conference. I totally agree. And I hope with him that the global meeting in Nairobi and the two that follow will turn out differently from what the ‘oil community’ wants.

Arnika has been working for a future without unnecessary plastics for a long time.