The organizations ALHem and Arnika, a Czech NGO, are defending the right to safe consumer goods for people in Serbia. Recently, we jointly tested school bags, handbags, and other PVC products purchased in Belgrade and found dangerous phthalates in them. We also work with young people who are learning how to run campaigns and engage in decision-making processes. We discussed the details with ALHem co-founder Jasminka Ranđelović.

How would you explain ALHem’s mission to someone who has never heard of your organization?

ALHem stands for Alternativa za bezbednije hemikalije — Alternative for Safer Chemicals. We are a civil society organization based in Belgrade. Our goal is to reduce the presence of toxic substances, especially in consumer products, thereby protecting human health and the environment. We monitor the use of potentially hazardous materials as well as compliance with various regulations, and we inform consumers about product safety. In the Western Balkans, we are probably the only civil organization focused on chemical safety, and we are active internationally, mainly at the European level.

You have been cooperating with Arnika for years. How did it begin?

About 15 years ago, I came into contact with the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), where Arnika has long been active. That’s how I met Jindřich Petrlík (one of Arnika's founders, editors note), and we began collaborating mainly on issues related to persistent organic pollutants. At first, Arnika was like an older brother to us — they helped us set strategies ranging from campaigns and public communication to organizational functions and fundraising. Soon, we began working together on a project dealing with toxic substances in consumer goods. Within IPEN, Arnika serves as the regional hub for Central and Eastern Europe and is a leader, not only in the field of persistent organic pollutants. We often receive the first updates about current developments in the field directly from Arnika.

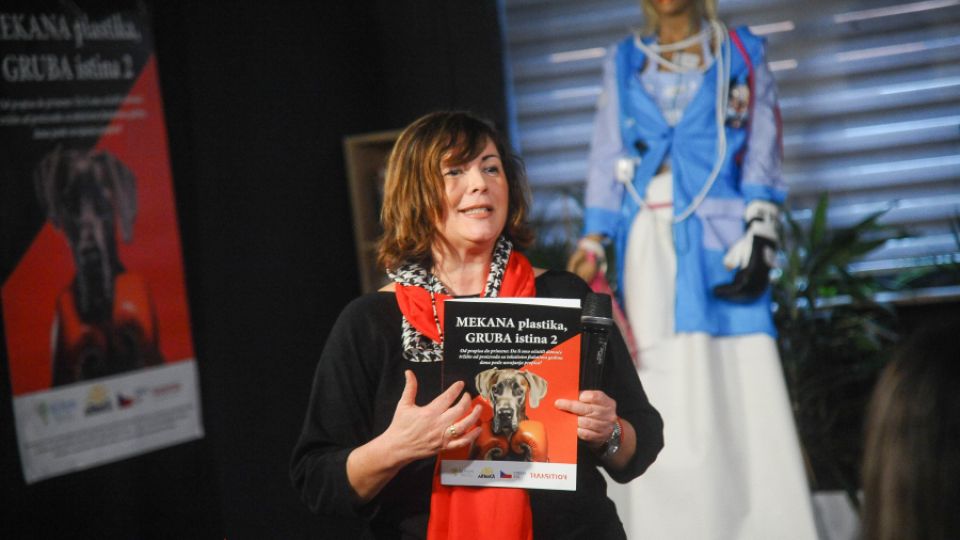

Recently, we jointly produced the study “Soft Plastics, Hard Truth 2,” which revealed a significant presence of phthalates in common consumer goods. How is it possible that such toxic substances are found in everyday products, and is Serbia specific in this regard?

The results are troubling not only because so many products contain toxic phthalates but also because of their high concentrations — in some cases exceeding legal limits by up to 500 times. Phthalates appear in products even in EU countries, but not to such an extent.

There are several reasons for this. Although we adopt European standards and bans, we lag about four years behind the EU. Industry exploits this by exporting goods that would no longer be approved for the EU market to Serbia and other Balkan countries. Regarding phthalates, Serbia tightened its rules following the EU model about a year before our study began. However, as we can see, that did not reduce their presence in consumer goods. There is a lack of coordination among government bodies responsible for enforcing regulations. Ministries do not have harmonized procedures, and it is unclear who is responsible for inspections. Inspectors are few in number and lack resources, young people are not motivated to take such jobs, and chemical safety is not a political priority. That is why we focus on raising public awareness and putting pressure on the authorities.

How interested is the public in the chemical safety of consumer goods?

Awareness — especially among young people — is increasing, as shown by several opinion polls. Late last yearwe ran an information campaign, including a press conference, and discussed consumer product safety on television programs. We reached almost one million Serbian citizens. This is significant. For example, after an article in Serbian Forbes discussed phthalates and the responsibility of authorities in detail, the Ministry of Environment finally informed us that it had started working with another ministry to determine who should bear responsibility.

Do institutions recognize the importance of your work? How are your relations with them?

Unfortunately, things have gotten worse. Until a few years ago, we had a constructive dialogue with the Department of Chemical Substances at the Ministry of Environment, but since last year, communication has reached its lowest level ever. Trust between civil society and the government is lacking. To make ministries react to our initiatives, we have to bring problems to the media.

Am I right that the atmosphere changed during the wave of protests that began across Serbia last November, after the train station tragedy in Novi Sad that claimed sixteen lives?

The situation had been poor for some time, but yes — it deteriorated further after the Novi Sad catastrophe. People, led by students, began protesting and demanding accountability. Society has lost trust in institutions and is dissatisfied with the government and systemic corruption. According to the latest survey by the NGO CRTA, nearly 60% of Serbians supported the protests even half a year after they began, and up to 80% supported the students’ demands. Civil initiatives, including ALHem, support the protest movement as well. At the same time, repression is growing, and organizations defending the rule of law or human rights face pressure from state institutions.

What strikes me about the protest movement is how long it has lasted. It doesn’t seem that people are giving up…

Yes — young people, in particular, are very aware of the seriousness of the situation and see no future for themselves under the current conditions. When university and even high school students go on sit-in strikes, it is important that broader society, including professors, supports them — and it does. Serbia is not only in a political but also in a deep social crisis — the kind that, in a democratic society, should be resolved through elections. I hope they will take place later this year.

By the way, do the protests have any environmental dimension?

They are not primarily about the environment, but there is a connection. Last year and the year before, major environmental protests took place against Rio Tinto’s planned lithium mining project in the Jadar Valley. These were driven by the same values as today’s student protests. Conversely, the lithium mining issue also highlights broader problems such as the lack of transparency in similar projects.

Setting aside the current turmoil — how do you see the next few years for ALHem in Serbian society?

I am very glad that in our current project we are working with young people, because they are the main drivers of change here. They feel strong and capable of pushing for change — including in environmental and chemical safety issues. The project is progressing well, and I believe it will be very successful. And what do I wish for in general? That Serbia will become a member state of the European Union in the coming years.

Jasminka Ranđelović

She studied biochemistry at the University of Belgrade. She has led the Department for Risk Assessment of Chemical Substances and Biocides at the Serbian Chemicals Agency, worked as an inspector at the Serbian Ministry of Environment, as an adviser to the Minister of Science and Environmental Protection, and as a consultant for the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). Since 2015, she has served as ALHem’s Program Manager.

The interview was originally published in the magazine Arnikum.